Out of Range: Part Three—Sowing Season

Out of Range is a five part, in-depth exploratory series that covers the the history of emo. From its first wave to its current revival, on to the impact of the word itself on language and fashion, it’s a primer for understanding the growth of a genre in its totality, alongside the technologies and changing cultural values that allowed it to flourish.

The following is part three of a five-part interview series with Tom Mullen of Washed Up Emo, a curator of emo history and, above all, an educator who has kept the dream of the genre alive through good times and bad times alike. Tom was gracious enough to offer his insight about the genre including its controversies and hidden histories.

Chapter Three: Sowing Season

Irony is a shield against truth and reality, at least in some form. In the case of the third wave, irony both as natural defense and a preconstructed aesthetic found its way into the heart of emo as a genre. There was, at the time, nothing more ironic than taking a genre known for its lyrical honesty and integrity-driven lineage, and turning it into a corporate branding.

It would be easy to immediately generalize the third wave as being composed of “sell outs.” It would also be easy to immediately argue against such a concept. Success, in any industry is at the mercy of an intersection between culture and commodification. That’s why there’s no such thing as selling out, there’s just a time and a place where chance and skill forgo a perception of integrity in favor of fiscal motivation due to changing cultural values. And culture, at least at the onset of the early 2000s, was in an odd juncture.

The third wave was subconsciously driven by a cultural climate that was surrounded by nebulous pains of uncertainty, as a growing conflict in the Middle East alongside the trauma of 9/11 haunted a generation. While, the fruits of capital and technological innovation led to a rapidly shifting landscape of portable technology. The early 2000s were an odd way to welcome in the third wave, oddly similar in premise to the tumultuous nature of the ’80s that surrounded the first wave’s own anxieties and experimentations.

Perhaps the burgeoning growth of the genre fit alongside an amalgamation of national insecurities derived from a music culture that was deeply warped by the tail end of the ’90s. Regardless of climate, the meteoric rise of the emo genre, alongside its impacts on language and fashion, was undeniable. It was official: For the first time emo was profitable, and its push to be “the next big thing,” and perhaps the last “big thing,” left the genre at an altar of misunderstanding and confusion that has at the least forever changed the genre and at the worst forever harmed the history, the term, and the significance of emo itself.

At the beginning of the early 2000s, emo found itself in a house divided, where for three years emo bands such as Brand New, Taking Back Sunday and Dashboard Confessional—who had inherited elements of the second wave—broke onto the charts only to be usurped by a record label re-branding of emo as a more accessible menagerie of pop punk with sometimes baroque stylistic sensibilities and garish fashion to match. The mutation of pop-punk masquerading as emo became indecipherable to mainstream culture, and its fashion soon became synonymous with a derivative sound.

Understandably, this sudden shift happened with an alarming alacrity. It could be that the genre’s growth so happened to line up with one of the most profound changes for marketing imaginable: the birth of social media. Sites like Pure Volume and MySpace eliminated the need to scour the world and record stores for like-minded sounds and similar acts. These were the new tastemakers. In premise, MySpace putting power or selection back into the hands of the user, allowing them to cultivate a personalized space for one’s own life, was enormously powerful. What it was however, was an immediate connection between corporate label-driven interest and a new metric that was used to target artists and potential consumers by means of measuring consumer habits. The emo bands of the third wave just so happened to be, like all popular music, a product that was consumed, packaged and measured accordingly.

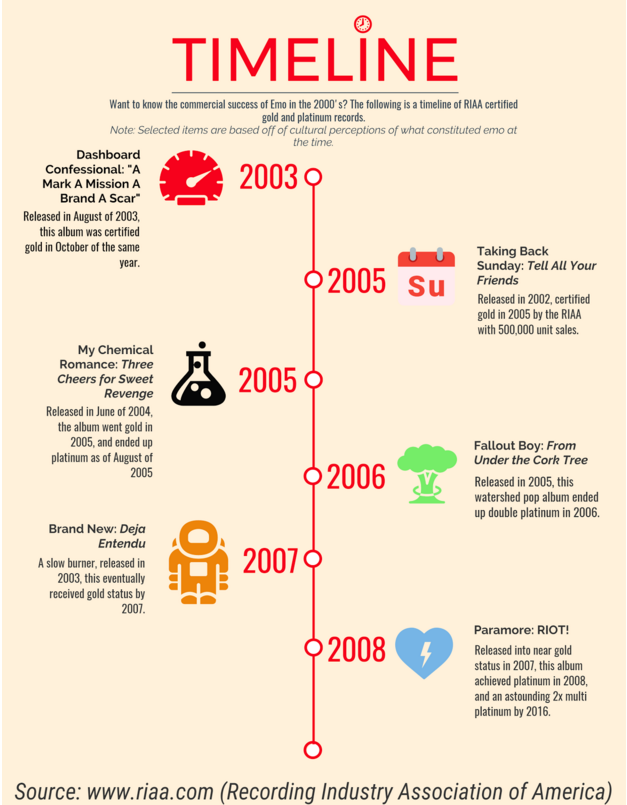

Billboard charts were dominated by Paramore, Fall Out Boy and Panic! At the Disco, pop-rock titans that shouldn’t have worn the mantle of “emo” but managed to acquire it while emerging from the Fueled By Ramen record label. It helped to forge a popular consensus that defined the genre’s fashion, sound aesthetic, and market appeal. Of course, using observable records from the RIAA, it’s easy to build a chart that shows the prominence of the genre using record sales from 2003 to 2005, showcasing the genre’s observable affluence.

It’s during this time of incredible financial and cultural momentum that a similar division is occurring within the genre. At the same time that the genre is becoming more and more profitable, some of the earlier third wave artists that helped pave the way for its massive growth find themselves apart from their genre. Artists like Brand New, for instance have managed to defy categorization, their sonic flirtations with indie and post-rock, alongside Jesse Lacey’s profoundly personal and philosophical lyricism on their masterful 2006 release The Devil and God Are Raging Inside of Me, helped cement potential for the genre to grow outside its comfort.

Once more, as if by fated circumstance, a similar galvanizing force comes into focus during this time, and their presence perhaps better informs us as to what emo came to mean for so many, yet what also stood as a terrible misunderstanding. The curse of “emo” was inescapable for those who received its branding, and My Chemical Romance’s seemingly improbable representation of the genre and their misguided association is still to this day, a discussion point argued by fans and critics alike.

My Chemical Romance could, in fact, not be further away from the genre itself, and lead singer Gerard Way’s condemnation of the term, is at both honest, yet ironically contradictory to their own success. Rolling Stone quoting an interview with student newspaper The Maine Campus found that Way stated “Basically, it’s never been accurate to describe us. Emo bands were being booked while we were touring with Christian metal bands because no one would book us on tours. I think emo is fucking garbage, it’s bullshit. I think there’s bands that unfortunately we get lumped in with that are considered emo and by default that starts to make us emo.” Effectively, the argumentative nature of the genre reared its ugly head once more, proving that semantics were still just as important as perception, exacerbated when My Chemical Romance’s lyrical content alongside their visual style became within popular culture the very definition of emo. Perhaps this was shaped by their bombastic music videos, or by their decidedly gothic style, they were soon designated as emo due to the lingering first half of the 2000s.

This did not interfere by means of profit, or in terms of popular appearance. Like many others before them, My Chemical Romance could not opt-out of their designation by fans and critics. Its effects were in some senses positive. Emma Garland, cultural critic and assistant editor of Noisey UK, reflected about the third wave and specifically what My Chemical Romance did to open up the necessity of discussing mental health in the open. Garland wrote, “My Chemical Romance and The Used were two of a whole host of bands loosely billed as ’emo’ who helped create a space where it was okay for people to talk about their problems when they felt like their parents, their friends, their teachers, and the world-at-large would either invalidate them or react with hostility. For all its melodrama, emo was a movement that (at least at its core) took those issues and those people seriously.”

Garland’s assessment of the third wave tackling burgeoning social and gender issues is accurate, while her furthered analysis of the third wave and it’s terms of discussing mental health paints a stunning retroactive portrait, Garland writes:

“In her 2011 academic research paper “Emo Saved My Life”, Dr Rosemary Lucy Hill, a lecturer in Sociology at University of Leeds, challenged the discourse of mental illness around emo and My Chemical Romance specifically, and found that gender was a large contributing factor in how the narrative was shaped. Her research found that women were automatically treated as victims of the music rather than fans who found solace or agency in its message.

“’Girls and boys are socialised differently and the conditions of their teenage lives are some what dissimilar,’ Hill writes. ‘Findings that young men use metal to cope with anger suggest that we could similarly explore My Chemical Romance fans’ reasons for listening to the band in the context of their reported self-harming and discussions of suicide. We need to listen to what the young women have to say.’ After doing so, Hill found that: ‘Rather than emo being a fashion that pushes them towards feelings of desperation, into self-harming, to commit suicide, it can help fans to survive mental ill health.’”

During the time however, popular conceptions of emo were mostly in negative association, and as the decade furthered along, the word began to accommodate the concept of displaying an exuberant and often negative outburst of emotions. It was better to be detached and ironic, lyrically and otherwise, but certainly not to confide with sincerity in one’s own emotions, an obvious perceivable weakness. Which, as one could surmise, forms a massive contradiction between the prior waves of emo and the latter half of the third.

As profitable and immediate as emo’s rise to success was, by 2008, the third wave’s prominence was coming to an end. Like all movements of culture devised and instructed by music’s growth, it rose and fell with the temperament of both economy and consumer interests. Its whimpering end wasn’t even a true end, insomuch as it was a coma, a quiet that calmly drained the interest from the public and focused it elsewhere. The bands that did survive, the largest ones who frequently went gold or platinum within both album scenes and single scenes, changed their sounds and narrowed their audiences in order to maintain relevancy. For many of these artists, this was a doomed experiment, an attempt at prolonging their life in the limelight. For others, such as Paramore and Fall Out Boy, their renewed success came with a willingness to diversify and change their sounds rapidly to accommodate fluctuating tastes.

Emo, for its massive and intoxicating success during its third wave, gained if anything a sense of compassion and acceptance in exchange for an altered culture stereotype. The cliche of the branding still lingers, culturally, linguistically, its connotation still forced through the veins of the genre’s newfound prominence and value. So as quickly as the popularity of emo fell away from culture’s obsessive grasp, the desire to once again invoke its capacity for change and its ability to build communities would once more come around, but not in the form of tired, stereotypical, overly derivative artists grasping at fleeting success, but instead with renewed vigor and endless inspiration, a sure renaissance lingered in the distance, just a heartbeat away as the cycle keeps on, endlessly.