Treble Roundtable: Life-Changing Albums

Welcome back to The Roundtable. Let’s get back to the conversation. In case you’re new to it, this is where Treble opens up to our readers about our individual experiences on a more personal level, without putting too much of a critical eye on it. Not that the eye ever shuts — this is simply a casual conversation. Got a question for us? Feel free to send it over to [email protected] with the subject “Roundtable topic.”

This week’s topic: In honor of Zach Braff’s return to film, we dust off an old chestnut from a key scene between him and Natalie Portman in 2004’s Garden State: What album changed your life?

Adam Blyweiss: I’ve completed my share of influential-album memes, so I could go to bat for a couple different releases that Changed My Life with capital letters. Yet my earliest musical tastes were defined by my parents—whatever pop vinyl was around the house, cassettes as birthday gifts, music video rentals, etc. Radio came next, but for a long time I was all about singles and styles rather than albums; the Top 40 landscape felt more diverse than it does now, I dubbed mixtapes off my rock station, and our urban station’s weekly DJ sets overloaded me with rap and early electro. Even my participation in many things indie, and my admiration of everything from Aphex Twin to The White Stripes, had to have a starting point. That came among high school peer groups, of course — back then I was a Monty Python silly-walking NERRRRRDDDD: I spent the first two years of high school doing science fairs, overlapped that with two years of Model UN, and then two as a choir and stage geek. I was surrounded by kids listening to music with a weird synthesis of humor, scenery, and politicking: We started with Weird Al Yankovic and eventually ventured deeper into actual college rock, into The Dead Milkmen and They Might Be Giants. I didn’t agree with everyone’s choices, but my closest friends and I definitely agreed on R.E.M. If we hadn’t heard “The One I Love” or “It’s the End of the World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine)” on Document we heard them and a bunch more on their IRS Records greatest-hits compilation Eponymous. It was my first connection to the band’s mystical and oblique artistry. As a pimply outsider student I totally got Michael Stipe’s picture with the oversized caption “THEY AIRBRUSHED MY FACE,” and while I was drawn in by his curiously fumbling lyrics (“Radio Free Europe,” “Driver 8”) I was held by his friends’ dusty grooves (“Romance,” “Finest Worksong”). They were one of the first artists I started actively following and reading about—a fair commitment in those pre-Internet days—and while two larger compilations eventually superseded Eponymous it jumpstarted me actually seeking out the artist’s back catalog. Despite all of my electro-speak these guys are my favorite band of all time and I consider Stipe an inspiration and muse.

A.T. Bossenger: It’s easy enough to come up with disappointing records or artists you took a while to come around on. But “what music changed your life?” For a music writer, that’s tough. I’ve already written about how strongly I identify with Arcade Fire’s Funeral, and I toyed around with the idea of discussing any pick of albums by Fugazi or Radiohead, two of my favorite bands of all time. But, in the end, I decided to go with something without the universal acclaim; not an album that changed life itself, but one that changed my small, rather insignificant life in big ways. When Tilly & The Wall released their debut, Wild Like Children, I was 15. Their distinct indie-pop was nestled somewhere between dance pop and the bizarre folk Saddle Creek Records artists (including Team Love co-founder Conor Oberst) had made so popular at the time. What struck me about Tilly was their relentless experimentation; despite their willingness to fit within a pop format, everything they did was uncompromising. There’s not really a strong pop flow to the record; it’s more like ten back-to-back singles, each with its own flair. They relied on a sole tap dancer for percussion, except for when they felt like using an iPod to play beats beneath their mostly acoustic set up. They played country-tinged ballads, except for when they felt like ramping up the anger on “Nights of the Living Dead” or stepping up the groove on “Perfect Fit.” They relied on female lead vocals, except for when one of the men in the band felt like writing a song. If they wanted to sing about bisexuality and sexual experimentation in 2004, they did. If they wanted to include a hidden track on an indie rock CD in 2004, they did that too. Tilly & The Wall did what they wanted and they did it damn well. Before Wild Like Children, I had heard plenty of records that I liked. But here was a record that sounded like one I would like to make, edgy pop steeped in collaboration and artistry. It wouldn’t be the last, or even the most important, but it was a great start to expanding a young musician’s idea of what a record could be.

Nicole Grotepas: Until I was in college, the music I appreciated and listened to was —how to put this delicately? — total crap. And when I say it was easy listening, it wasn’t in an ironic, Jack-Black-wearing-a-Yanni-concert-T-shirt-in-High-Fidelity type of way. That was what my taste consisted of back then: the hits of Rod Stewart (not the edgy, early Rod Stewart), Peter Cetera once he shed that dead-weight band (Chicago), and Michael Bolton with those steel bars wrapped all around him. A few years post high school, I ran up against Modest Mouse. It was my first brush with them. The Lonesome Crowded West was just out and someone in the CD store where I worked played it over the store system. But it was difficult to listen to and I didn’t like my “art” to be hard. For me it was loud, ugly, and unmusical, and trying to enjoy it was like trying to appreciate a wart or a huge mole on your blind-date’s face. So yeah, I didn’t get into it. I was too busy lip synching “Glory of Love” as I danced around the empty shop. How could I appreciate anything that wasn’t easy on my ears?

Later on, during a rock climbing trip with some friends, I was a captive audience in a Hyundai Sonata where I was forced to listen to The Moon and Antarctica and Building Nothing Out of Something. This was tantamount to being shoved into a chrysalis and urged with a cattle prod to transform. I woke from that with new eyes: music doesn’t have to be beautiful to be amazing (a naive concept to be sure, but I was young). From there, my music appreciation exploded. It was like a ME renaissance. I remember discovering Leonard Cohen. I cried the first time I listened to “Suzanne.” I got my hands on a copy of Astral Weeks and almost died when I heard “Madame George.” The most valuable thing I gleaned from this time was that quite often, the top-40 stuff isn’t necessarily an artist’s best.

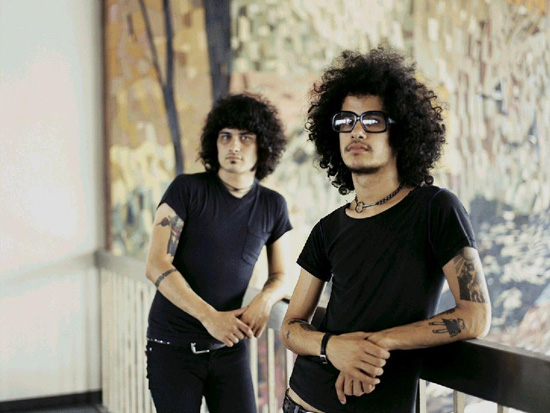

Giovanni Martinez: There are many albums I own that have been critical to certain points of my life — from dealing with a bad break up to the loss of a loved one, there are albums that are connected to those emotions and events. But, there is really only one album in particular that shaped my life and my current direction, and it was The Mars Volta’s De-Loused In The Comatorium. I had no prior knowledge of Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and Cedric Bixler-Zavala’s previous work in At The Drive-In, and only knew they had broken up and then formed a new band. I learned about them from my cousin, who wouldn’t stop talking about how great they were, and I managed to get a burned CD-R copy of the album. Eventually, I would score my own legit copy and that sucker never left my Discman. At 14 years old, that album meant the whole world to me. I picked a strange time to listen, too. While most kids my age were listening to a lot of shitty hardcore bands and then later forming their own shitty hardcore bands, I was alone, trying to master Omar’s guitar parts, but to no avail. I had never heard anything like it before. Part of it was reminiscent of Pink Floyd and small bits of Santana, but my exposure to prog rock was very limited. I knew of King Crimson, but that was it. I can definitely tell you, De-Loused opened up a whole new world for me. From reading most of their interviews, I learned about what books the two songwriters in the band read, what films they watched and what music they listened to in their spare time. Their tastes seemed so wide and diverse, and as a listener I followed in their footsteps. One aspect I take away from The Mars Volta is their ability to weave a very intricate story about their deceased friend, Julio Venegas and how they were able to portray it in the form of an album. And in turn, that’s how I got involved with film and an appreciation for all types of music. I don’t listen to De-Loused as much as I used to and sometimes I revisit it. But De-Loused helped me discover more about my world and myself and that’s one experience I can take away from it.

Paul Pearson: I, too, resist answering and asking the question “What album changed your life?” None of them changed my life. Not the way marriage, child-bearing, a botched appendectomy or a quail hunt with Dick Cheney changes one’s life. But there was an album that tectonically shifted everything I thought about music: Tom Waits’ Swordfishtrombones from 1983. I’d read Don Shewey’s review in Rolling Stone: “Tom Waits’ new album is so weird that Asylum Records decided not to release it, but it’s so good that Island was smart enough to pick it up.” For some reason that, and having already owned Heartattack And Vine, convinced me to spend my allowance on it. It came out during an exceptionally pop period in music, when Thriller was dominant and many hard-edged new wave refugees were being remodeled. I didn’t realize you were allowed to make music like Swordfishtrombones. The percussion sounded like tin cans and oil kettles. Waits didn’t sing so much as he hectored, conspired and just woke up from a nap. Every song was a short story that read like a Flannery O’Connor novel as seen through the eyes of an exiled Italian film director. And somebody left the studio door open and let in a marching band. My teenage astonishment over what I was hearing turned into real affection, and that turned into taking a few more risks with my listening habits. It changed my turntable’s life.

Jeff Terich: Most of us at Treble probably came to music in the same way — parents, siblings, friends, radio, etc. We went from simple pop music to punk rock to weirdo indie stuff, and it all made perfect sense for the age and the year in which it happened. But the funny thing is that the one piece of music that I can remember stopping me dead in my tracks and reshuffling my entire perspective actually circled back to the beginning: It belonged to my dad. I used to do some part-time work for him during summers in high school, and most of the cash I earned, I spent on music. New, old, whatever — I was rapidly expanding my collection and I had cash to burn. In his office, however, he’d mostly listen to jazz records, which I often enjoyed but never really gave much intense thought. I remember offhand mentioning that Miles Davis‘ Bitches Brew sounded pretty cool, which prompted him to put on its predecessor, In A Silent Way. In that moment, my fairly conservative pop-centric definition of music no longer applied. You didn’t need verses, choruses, hooks, or really even something to be fully written out. You could just follow a groove — a feeling. It sounded so alien and strange to my ears, but there was a melodic core about it. Yes, it was weird, but it was beautiful. One listen hooked me, but it’s not as if it all totally made sense. I had to listen to it again, soak in all of its various moving parts — I had to crack its code. In a Silent Way changed my life not because it introduced me to a new style of music, but because it taught me that you can engage with something that challenges you — that makes you look beyond the surface. Fifteen years later, I do get a sense of instant satisfaction when I hear it, but I treasure it because of the journey it took to get there.

Alex Zaragoza: I grew up surrounded by Motown, The Beatles and Spanish pop typical of any Mexican household thanks to my parents, as well as hip-hop courtesy of my brother and sister. That’s not bad stuff at all. It’s amazing! But because I was a dingus that didn’t quite get music (I’ll admit I actually rooted for “My Heart Will Go On” to beat Elliot Smith’s “Miss Misery” at the 1998 Oscars just because I thought Leonardo DiCaprio was cute. I’ll hand in my Treble/life resignation now), I didn’t quite know how to appreciate music in general. Once I entered high school, I started the long and painful process of figuring out what I was into and inevitably who I was. Then one day in AP European History class I met Monica, who would not just become my best friend but my cosmic sister. Unlike me, Monica grew up with music that was just so fucking cool. While I was choreographing awkward dance routines to Mariah Carey’s “Dreamlover” in my bedroom in 4th grade, Monica was writing essays for her class on her favorite band, Pulp. One day Monica suggested we trade CDs to introduce each other to bands we had never heard of. I handed her Portishead’s Dummy and she handed me Blur’s Parklife. I was never the same again. It kicks in with “Girls and Boys,” an upbeat, punky pop jammer about life in middle class England that somehow made a teenage girl from Tijuana dream of dancing at a dingy London bar. “End of A Century” made me want to learn all the lyrics right away so I could belt along with Damon Albarn. That entire album gave me a true introduction in Britpop beyond thinking Trainspotting was cool and watching the “Champagne Supernova” video in between episodes of The Grind. From then on I was hooked on Britpop and became a major anglophile, introducing funky track jackets and sneakers into my wardrobe, dancing until 4 a.m. to the genre’s biggest hits at a Tijuana bar called Porky’s and eventually moving to England for a year in college, where I met a British dude I eventually married and later left. I truly think all of that can be traced all the way back to that moment where I popped in Parklife into my Discman and pressed play.