I lived through a time when Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Cats was a cultural phenomenon. There is a point in the show where the actors chant lines based on T.S. Eliot’s “The Naming of Cats,” and their use of the word ineffable near the end stuck with me. I didn’t know at the time what it meant or if it meant anything at all, considering the amount of nonsense language Eliot used in the poems inspiring the show. Turns out it’s a cool old word that means: you can’t put something into words. To have an ineffable quality is to be so good, or so mystical, or just so much of something, that you cannot accurately describe it.

In my head, in modern parlance, I convert ineffable to un-F-able, which then of course has to be converted to unfuckwithable. It’s a stupid, silly thing, really. Ineffable is not a meme, it has legit Latin origins, dammit.

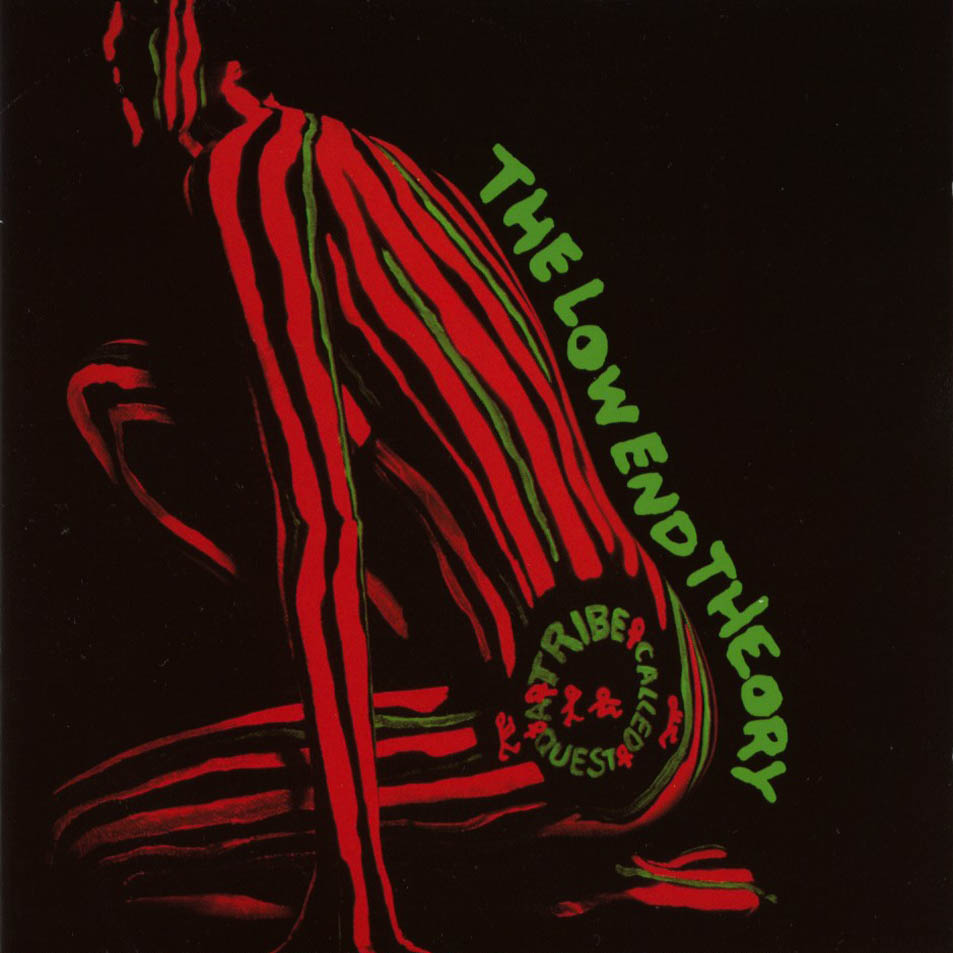

In the meantime, I’ve been sitting here with a Treble 100 piece paying tribute to A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory in my drafts for what feels like the entire fucking winter. I can use individual words to describe the album. Maybe string a few together. Godhead. Dope. Masterpiece. Fun. Joyous. Beats. Rhymes. Life. Unfuckwithable. The rest of the essay, however? Hopefully it flows down below from this point.

It’s all very zen and existential: Because The Low End Theory is unfuckwithable, The Low End Theory is ineffable. Hard to put into words for some. Maybe even impossible for others. I mean, I could recite Wikipedia chapter and verse about Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Phife Dawg, Jarobi White, and Q-Tip’s Queens origins, their place in and relationship with the Native Tongues crew, where they came and wanted to go from with People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm. I can tell you now it wouldn’t feel right, and I might get some of it wrong. To this day I’ve never listened to Instinctive Travels front to back—hell, I’m far more familiar with We Got It from Here… Thank You 4 Your Service. Some fandoms are just like that, all 2001: A Space Odyssey: a monolith getting all of the attention, surrounded by wasteland.

The Tribe—at least as I will always know them, psychically daubed in black, red, and green body paint—always felt far more laid back, more minimal than even their giddy Native Tongues crewmates in De La Soul. So The Low End Theory from note one approximated a smoky jazz club full of whispered secrets and enthusiastic riddles. Sounds and loops were simple, and the raps largely focused on exploits with friends and lovers with the occasional hint of Black liberation. ATCQ did strategically lift one important thing from the masterminds over at Def Jam: the featured live performer. Beastie Boys had brought in Kerry King for “No Sleep till Brooklyn,” while Public Enemy teamed up with Branford Marsalis for “Fight the Power.” Quest’s ace in the hole was prolific jazz artist Ron Carter on double bass on “Verses from the Abstract,” and to their credit the production from Muhammad, Q-Tip, and Skeff Anselm created the illusion that Carter was actually all over the album. Ron Carter? Unfuckwithable.

From (and because of) the late 1980s to the early 1990s I devoted a lot more energy and research to PE and the Beasties. Maybe it was their more complex plunderphonics that intrigued me? I’d been reading a lot about Public Enemy, and through reviews and interviews their sampladelic mystery was unraveled, the alchemy of Miles Davis and Prince and Slayer made clear. Beastie Boys were unapologetic sonic starfuckers, sampling the hits on Licensed to Ill and just about everything else on Paul’s Boutique. So one of the things I love about The Low End Theory is how, more than most rap albums, it made me want to track down what had been dug out of the crates. It still does! I can acknowledge ATCQ’s Grant Green and Last Poets bonafides, but now that we have resources like Genius and WhoSampled I remain on the lookout for their other sources in the wild. These grooves? Unfuckwithable.

If I’m being honest, some of the lyrics themselves can’t help but be a little dated. New listeners likely won’t know the importance of a skypager (“You leave code 69, that means you want some [cock]”) and “The Infamous Date Rape” addressed a then-growing social issue in pretty ham-handed fashion. Still, the rap interplay of Q-Tip and Phife Dawg feels just this side of effortless, making you forget Jarobi’s disappearance from Quest’s picture until well into the 21st century and that Phife himself almost left the group permanently as well after Instinctive Travels, following a diabetes diagnosis. Q-Tip had coaxed him back for what would become The Low End Theory, but Phife constantly had to fight to get a verse in edgewise throughout the album. Tip has five solos to his one (“Butter”), and starts and ends most of the duets—real talk, this could have been Amplified. But the duet that was the album’s legendary lead single, “Check the Rhime,” clearly established the two as equal talents even if they weren’t equal participants. The sexy, sultry one and the cute, neurotic one: an ineffable partnership.

If there was one thing Quest booked here that some of their harder-hitting contemporaries did not, it was the posse cut. And not just the posse cut, but the posse cut to ether all others. Native Tongues would show up and trade verses throughout their formative years and albums, and The Low End Theory includes the cautionary music-industry tale “Show Business” with Lord Jamar and Sadat X of Brand Nubian and Diamond D of DITC. (“Time pass and your ass say, ‘Where’s my loot?’/The reply is a kick in the ass from a leg in a boot.”) But out of sessions and recorded takes that included Jarobi, manager Chris Lighty, and members of both De La Soul and Black Sheep, Tribe settled on a version of album closer “Scenario” that focused on them and their friends in Leaders of the New School. On an album that was so good it led to management changes that eventually broke Native Tongues, they closed their collective boast with a microphone hand-off to Busta Rhymes that eventually broke LONS. “Powerful impact/Boom, from the cannon”—just unfuckwithable flow.

I don’t know if The Low End Theory is the perfect rap album, or even just a perfect rap album. I do know it can run hard or run tender, and sometimes it runs both at once. Its boom-bap of drum, bass, and voice, with an occasional hook, was either simple or deceptively so—truly musical like a jazz ensemble, fitting together like gears, each cut and each cut’s tracks individually memorable in a way that few other releases have ever mustered. And more than musical like a jazz ensemble, this work properly hybridized jazz and rap moving forward for all time, actual innovation alongside the borrowing of good ideas from others or doing stuff better than their contemporaries.

Without A Tribe Called Quest there is potentially no path forward for Digable Planets to be “Cool Like Dat,” by extension no Shabazz Palaces, and we have to wonder about the oeuvre of artists like Moor Mother too. There’s no template for Guru’s Jazzmatazz, Vol. 1, or for The Brand New Heavies’ Heavy Rhyme Experience, Vol. 1. Maybe The Roots are big in Europe, maybe Us3 never breaks in the States. Is acid jazz even a thing? Are Portishead and trip-hop? Whither band-based rap—what of your K.Dot, your D’angelo, your unplugged Jay-Z? Ponder, for a moment, the butterfly effect of a world without The Low End Theory. Ponder the ineffable.

A Tribe Called Quest: The Low End Theory

Note: When you buy something through our affiliate links, Treble receives a commission. All albums we cover are chosen by our editors and contributors.

Treble is supported by its patrons. Become a member of our Patreon, get access to subscriber benefits, and help an independent media outlet continue delivering articles like these.