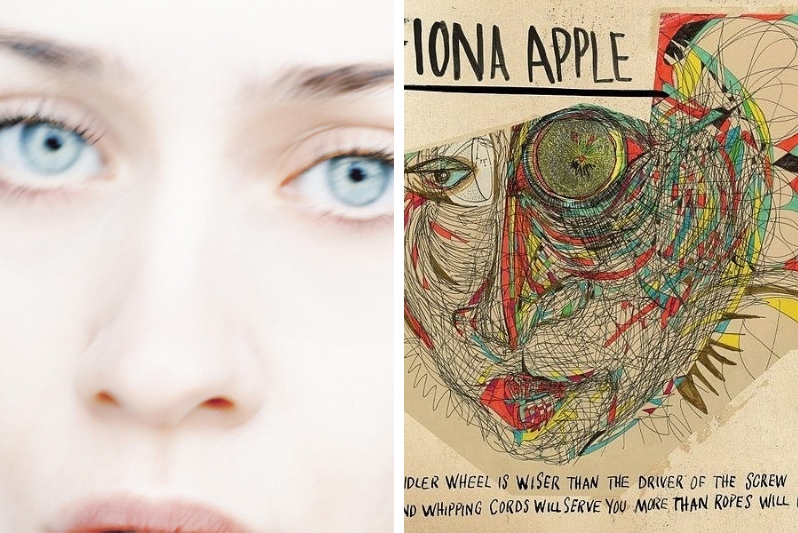

Pick Your Poison: Fiona Apple’s Tidal vs. The Idler Wheel

Why do we as music fans deify musicians? More so than the fiction writer or the poet, or even generic artists (visual or performing), musicians earn a distinct reputation as the transmitters of emotional languages—the kind best not spoken, but instead sang, played, felt. No other musical artist embodies this myth better than Fiona Apple, who, besides her notoriously reclusive habitual practices, has released some of the most positively lauded music of the past twenty or so years, from her teenage debut album Tidal to her blatantly masterful album The Idler Wheel is Wiser Than the Driver of the Screw and Whipping Chords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do. The two albums are uniquely distinct, each capturing a whirlwind of Apple’s artistic prowess.

But Tidal and The Idler Wheel are two disparate beasts. From the debut to the latest album, Apple’s production devolved—not the quality of the production, but the aesthetic (both of which are uniquely particular). Tidal is by all means a razor-sharp studio album, generating six singles (“The First Taste,” “Shadowboxer,” “Slow Like Honey,” “Never Is a Promise,” “Sleep to Dream,” and “Criminal,” the latter notoriously penned in a matter of minutes to please Columbia Records) and featuring more than a dozen session musicians; the outcome of Tidal is playful, magnificent, and punctual, albeit structurally and musically verbose. There is a restless nature inside of Tidal, but the cause of this could be chalked up to its position as a debut—Apple was still finding the voice she has become lionized for. Somehow a 19-year-old kid from New York City came up with a refreshing concoction of energetic sophisti-pop and cool, vibraphone-soaked jazz not shy of Milt Jackson’s periodically minimalist wheelhouse—sprinkle in a bit of sawtoothed prose-as-poetry and you have yourself a tour de force of ‘90s uncertainty, or, art for art’s sake.

And then we come to The Idler Wheel is Wiser Than the Screw and Whipping Chords Will Serve You More Than Ropes Will Ever Do. There’s an inherent inequity comparing an artist’s debut album to their latest. In the span of 15 years, Apple found herself shoot to pop stardom while remaining the strange, musical presence she is and has always been at heart. Tidal and The Idler Wheel hardly sound like they were made by the same artist if not for that directly idiosyncratic vocal delivery Apple is so capable of. On one hand, you have Tidal, by all means an exquisite execution of high-minded musicians collaborating behind a revelatory vocal force; on the other, you have the abstract and sparse The Idler Wheel, which, besides the fact that it was recorded, is music that could have been written and performed nearly 200 years ago, if not longer (the kora, a sixteenth-century West African string instrument even makes an appearance at some point). There is nearly nothing used on The Idler Wheel that wasn’t invented prior to the 20th century. The songs on The Idler Wheel, which range from hypnotic piano ballads (“Jonathan,” “Left Alone”) to surrealist, thundering vocal harmonies mixed and mended to create a nauseatingly gorgeous conceptual closer (“Hot Knife”), each of which are supported by a creeping, rumbling percussive background (courtesy of real human thighs and ancient Timpani drums that date back to nearly 6 A.D.).

More importantly, however (and this is the case for all of Apple’s music), is the poetry that narrates each of her songs. Read any lyric of any artist aloud, and it’s bound to sound generic, dry, prone to cliche. Not for Apple. Read any of Apple’s lyrics aloud and they will transport you into a world that is dark, undoubtedly literary, and grammatically nuanced. The Idler Wheel is the superior outlet of her poetry: “My scars were reflecting the mist in your headlights / I look like a neon zebra shaking rain off her stripes / And the rivulets had you riveted to the places that / I wanted you to kiss me when we find some time alone” (“Anything We Want”); “My ills are reticulate / My woes are granular / The ants weigh more than the elephants / Nothing, nothing is manageable / So couldn’t we skip the valedictories? / I can see a the door there / Shut it and forget my number” (“Left Alone”). That’s not to say that Tidal isn’t a poetic endeavor: “Is that why they call me a sullen girl, sullen girl / They don’t know I used to sail the deep and tranquil sea / But he washed me ‘shore / And he took my pearl / And left an empty shell of me” (“Sullen Girl”); “You moved like honey in my dream last night / Yeah, some old fires were burning / You came near to me and you endeared to me / But you couldn’t quite discern me” (“Slow Like Honey”). But even these moments of poetic enlightenment still appear—in comparison to the expertise on The Idler Wheel—sophomoric, drenched in romanticism.

On Tidal, Apple’s besmirched tessitura isn’t just a glimpse of what Apple would become—it’s a testament to the authentic talent Fiona has possessed since she was a young teenager. But it’s also a sophomoric undertaking of a conceptually vague premise—where Tidal drowns in excessive and grandiose arrangements, The Idler Wheel’s maturity and psychologically grueling aesthetic somehow manage to float above the loose moments of Tidal. At the end of the day, the two albums came from two practically separate entities—the naive, teenaged Apple on Tidal, the seasoned veteran painfully honing her craft on The Idler Wheel— but the pop-oriented nature of Tidal sags below the enduring prowess of The Idler Wheel.