The Rush Catalog Part Three: Signals to Hold Your Fire

Rush experienced a sea change in 1982. Moving Pictures, their last studio album, and live album Exit… Stage Left were major breakthroughs for the band, especially from their perspective. Their fusion of their laser-tight prog rock and heavy metal theatrics with new wave—a punk rock reclamation of prog ideals—had produced a record that wasn’t just good but a new and proper beginning. Rush have since discussed that, in a perfect world, Moving Pictures would have been their debut. That’s said not out of scorn for their earlier work, which they still peppered into setlists in years to come, but instead a reflection that those records were more indicative of a band cutting its teeth on the hard rock, heavy metal and prog of the day, still yet to have found a voice of their own. Permanent Waves was an experimental gambit, a gesture in that direction, but Moving Pictures was its fulfillment, an album that opens with futurist neon-tinged prog rock seguing into the various explorations of new wave and ska in a prog context that would come to define the entire future of the band.

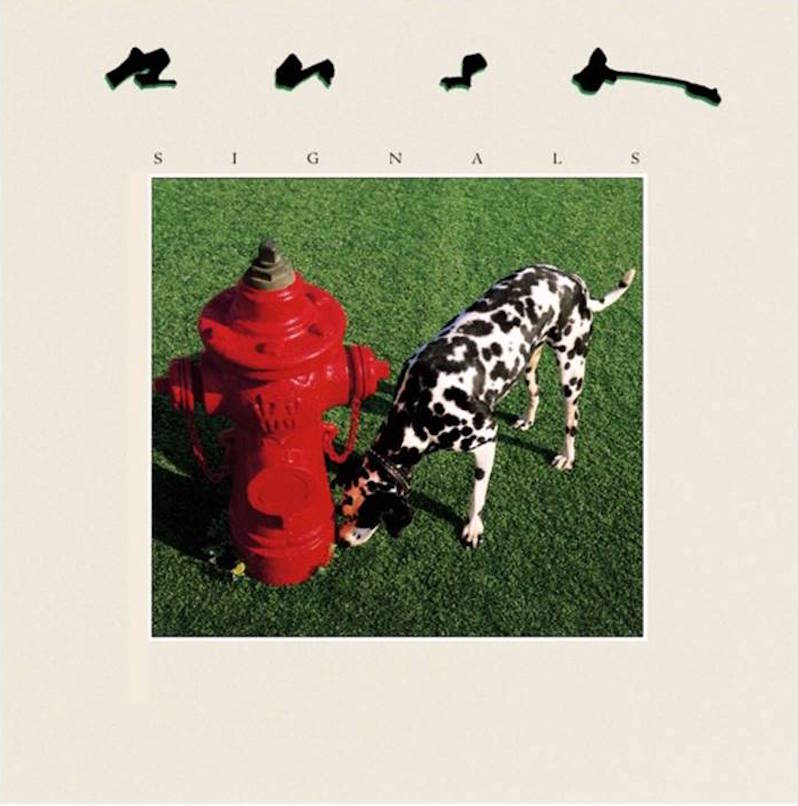

Signals

Signals might have looked very different had, while making of A Farewell To Kings, Rush enlisted a dedicated keyboard player as they had briefly entertained. That pivotal decision, to ardently remain a trio, which they took to the natural end of the group’s life, would strongly define this era of Rush’s music. Keyboards dominate opening “Subdivisions,” the second of such in their career following “The Camera Eye” from Moving Pictures; one can only imagine what contours the song may have taken had that now-iconic keyboard part been handled by a dedicated player, freeing Geddy Lee up to write another iconic growling bassline. It’s a recurring thought you have at some point when sitting with this period of Rush’s career, a period where to many fans, their obsession with keyboards threatened to derail the promise and grandeur of a band that dared to make outre prog rock in the era of punk and new wave. There is always the lingering ghost of what we know Lee can do on bass when the group diverts its attentions to the retrofuturist realm of synthetic music and those uniquely cybernetic vistas, like the flicker of a CRT virtual display or the gnostic lightning of pixels flaring to full-color on a dying screen.

The problem with those fixations on their past, however, is that they deny something that to everyone else is fundamentally undeniable: “Subdivisions” is not just easily the best song on the album and the best song to kick off this phase of the band’s career (its placement as the first song on the first record following Moving Pictures was never a coincidence; it’s a mission statement), it’s one of the best songs of their career. There’s a good reason why it was played at nearly every single show on every tour from the moment of its inception forward, being a musical masterclass in alloying the progressive inclinations via time signatures and panoramic, cinematic chords and celestial melodies against the cybernetic New Wave future, the synths indicating the wild impossible dreams of the child in the dead-culture capitalist hellhole suburbs and the driving chords and sullen rock of the choruses matching the despairing sense of being trapped. This is paired against a set of lyrics that is perhaps drummer Neil Peart’s most feverishly intimate, suddenly dropping all veils of literary diffraction or obscuring philosophy for a pure and revelatory image of where he stands, a boy with dreams perennial frustrated by the shape of the world that capitalism and the Cold War had given him. He hadn’t yet quite fully shirked the lingering conservatism latent in his libertarian ideology, but this almost confessional level of intimate portraiture of the emotional experiential core of why he cleaved to people like Ayn Rand and the sort would prove to be the lifeline out of that wretched ideology. The band were just entering their 30s, a common time of reflection over the lurking core that generated the illusory veil of self we cloak ourselves with; that he had this sudden insight to chronicle not a fantastical version of his thoughts and their extensions but instead a radically honest portrait of how it felt to grow up as a small boy in the suburbs of the west in the ’50s and ’60s and the nightmares those presumably happy homes contained would prove to be the spark to ignite his later universal empathy, the common ground that uplifts people out of conservative thought, politics and ideology.

“The Analog Kid” at first blush appears to be a continuation of the certain broad-hearted, car-friendly driving prog rock the group had tapped into on Permanent Waves with its finger-twisting rolling triplets on the guitar and soaring vocal. But then the chorus comes in, all synthesized choirs and suddenly the tone of the guitar shifts to the sharpness and reverb you might expect on a New Wave record but suddenly much more abstract, like breaking through into a kingdom of clouds and sunlight. The turn to minor key tonality on the bridge section feels like an injection of the simmering heat and frustration in the child’s dreaming heart, madly in anger with the barriers surrounding them. The song erupts into a solo like lightning before returning to this bridge again, only more fervent this time, no longer a sullen rumination but instead a paean, an oath, a prayer. It has a powerful dramatic arc, chronicling the boy from the lyrics of “Subdivisions” but here from a different angle, the driving rolling triplets verses married to the sense of adventure that youth and escape to the city provide while the cloudy synth choir chorus replicates the serenity and heart-alight sentiment of finding something you love (presumably, given Rush’s history of framing concepts around this experience, the feeling of making music). The increasingly passionate sullen C section that ends the song, declaiming “too many hands on my time, too many feelings / too many things on my mind“, crying out in frustration that “when I leave, I don’t know what I’m hoping to find / and when I leave, I don’t know what I’m leaving behind” seem consumed by grief, a grief of having to lose one’s home to find their home and the terror of youth where you have to hurl yourself into the emptiness of the world and life, disintegrating your stability, all to take the risk that might generate for you a life of your own.

It’s striking on “The Analog Kid” how sharp and programmatic the lyrics are. A great deal is said of Peart’s lyrics, but those sentiments tend to favor his more philosophical ponderings. It would be imprudent and rude to say that those are somehow valueless, but it’s striking that we don’t see more favor given to verses like “The fawn-eyed girl with sun-browned legs / dances on the edge of his dreams / and her voice echoes in his ears / like the music of the spheres.” This is everything that Rush haters think the band isn’t: an intimate and clear portrait of a specific moment, a boy laying back in bed with a record on staring at a poster on the wall or the artist on the sleeve, imagining the experience of making music, heart burning with the passion to replicate those long dreamed of images, all set to beautifully composed line sung well.

Signals is, in fact, a closet concept album. Rush opened up about as much shortly after the record’s release when Greg Quill of Music Express pressed Peart on the topic shortly after its release. The notion isn’t all that hard to grasp; the obvious pairing of songs like “The Analog Kid” and “Digital Man” gesture to at least one connection, not to mention the way the songs generally tend to arc from childhood to adulthood over the course of their span. It is a mature approach at concept, doing away with fantastical premises (no knock to genre fiction), instead replacing it for a loose coming-of-age narrative that seemingly charts the group’s understanding of their own history. Songs like “The Spirit of Radio” and “Limelight” from previous records seemed already to be more explicitly exploring their experiences while pieces like “Tom Sawyer,” “Freewill,” “Vital Signs” and “The Camera Eye” showed a group making a stark and deliberate turn away from the fantastical to at last address the contexts of their lives, society and culture on its own terms instead of veiled allegory.

We have to recall that, despite protests of certain staid conservative rock fans who would have liked to see the genre frozen forever, figures no less illustrious than Robert Fripp, Frank Zappa and Brian Eno were embracing this new terrain. That Rush would make a concept album was not a betrayal of these new expanded and evolved ideals but a fulfillment of them, proof that the musical and conceptual ideals that drove the band could survive and only be strengthened by responding to fair and valid critique rather than shirking away from them. That they’d then obscure this coming-of-age conceptual thread indicates as well the first clear instance of how the group would come to use conceptual frameworks in almost all of their albums from this point forward, the concept functioning more as a frame to make sure all of the songs properly hung well together. As much as Moving Pictures can be credited with Rush finding their own voice, these formal experiments coupled with their deep success (Signals is often cited by a certain sect of Rush fans and critics as the best, although this admittedly can be said of a few of the group’s albums) proved just as pivotal, proving the worth of their continued exploration of their actual honest-to-god progressing progressive music.

“Chemistry” is a song that likely could not have existed prior to this record. Its scope is arena-sized, wielding a vast lasershow keyboard sound against almost matching guitars in a manner almost evoking similar work from contemporaries like Journey. The pre-chorus features an eerie synth voice that is perhaps a bit too arthouse for what bigger rock bands at the time were doing but the arena-conquering power of the song breathes out like a dragon’s fire. Arena rock at the time was also a long-lost child of prog, with groups like Styx having started as functional American clones of Yes, Journey having started as a mostly-instrumental prog/fusion spin-off of Santana’s band and Foreigner having been primarily staffed by former members of groups like King Crimson. Rush wisely don’t try to play too arch on “Chemistry”; they clearly love the format and wish to do it justice as best they can, bringing their cerebral arrangements and unique instrumental voice (only Alex Lifeson could have played this guitar solo) to a domain that only a few albums ago they would have feared to tread.

“Digital Man” fulfills the conceptual thrust began on “The Analog Kid.” Here the group delves deeper into their ska and reggae interests spurred on by The Police, but here performed more commandingly. Geddy Lee’s vocals, for instance, no longer resemble a bad, borderline offensive pastiche of reggae mannerisms, instead more fluidly delving into the groove of things, while his bass playing is at its most expressively funky (you’d never have thought to describe Rush in that way prior to now) that he had ever put to tape. Lifeson here approaches guitar more as a coloring and rhythmic agent, laying wide slashing chords as an almost jazz-like expressive palette against which to let the bass-and-drum driven reggae groove evolve. His solo approximates ideas he’d toyed with on Moving Pictures but doesn’t feel outdated against the backdrop of their evolving sonic palette, instead feeling almost like a genetic link, an indication that they were still the same three excitable and exuberant rock players even in the midst of joyful experimentation.

Side two opens with “The Weapon,” part two of the three-part “Fear” cycle being released in reverse. (A fourth part would arrive decades later.) Here they build the song around the guitars and synthesizers, largely giving them a motorik interplay of interlocking figures over a strange and mechanical beat. The rhythm was largely devised on a drum machine to deliberately sound as inhuman and mechanical as possible, like a breaking and obscure machine attempting to approximate a four-on-the-floor disco pulse, which Peart then had to learn to replicate. The results, up till the bridge at least, are a cerebral pop-rock tune, where smart arrangements paired against smart lyrics about the social use of fear as a rattling weapon further the argument of Signals as perhaps Rush’s most human records. The bridge is where things get spicy again, however, taking a radical turn for an even more explicitly prog motif if already you weren’t convinced that this kind of thing counts. Suddenly a reggae-inspired hi-hat driven groove gets laid against disco bass drum and reggae/Carribean tom/snare accents while the synths and guitars decide to span out in abstract paints, throwing almost formless exploratory color, before a guitar thread is discovered just as Peart shifts into a backbeat, ready to bring the song back to earth with a recapitulation of the opening grounding musical statement just as they shift into a final chorus.

Despite the embrace of new wave, reggae, synth/electronic music and abstract textures on Signals, it is still always a bit shocking to encounter “New World Man.” It is purely and simply a reggae-flecked pop-rock number, where the only traces of prog are the strange fluid washes of synths that linger in the background as ear candy in the midst of an otherwise driving guitar/bass/drums trio rock number. It is also, perhaps more shockingly, arguably the best song on the album. Rush had undervalued Geddy Lee’s vocal abilities for a number of years, relegating him to Robert Plant imitations despite having a warm and sonorous voice and a great grasp of drama and when to really push with all of his might, all of which is on strong display here. The group had already proven with songs like “The Spirit of Radio” and “Limelight” that they could write absolutely thrilling pop-rock, music that was as hooky as it was instrumentally demanding, as approachable to a lay listener as it was dappled with the richness of musical thought of prog. That “New World Man” would indicate most strongly the future direction the group would take functionally until the mid-’90s makes perfect sense; even in the midst of an album of masterful songs, some of the very best of the decade from Rush or in fact any other band for that matter, “New World Man” feels like a breath, a crystal, a perfect synthetic hybrid of their strengths.

It’s also notable for me in that after years of writing Rush off for specious reasons, this was the song, especially its performance on Rush in Rio, that finally caused me to seriously reconsider my position. It’s the perfect antithesis to everything you are told Rush is; its lyrics begin to at last strongly decry Peart’s former conservative libertarianism, instead taking on a more worldly sentiment that likewise acknowledges its own faults and foibles, all married to a hooky but still tremendously demanding song. To say it opened my eyes would not be enough. At the power of its grace, I fell in love. One of its sentiments, “Learning to take the heat of the Third World man,” seemed to be prophetic, indicating the avenue via which Peart’s politics would eventually evolve to the bleeding-heart left-libertarianism he would hold in his later years, emboldened by his later travels via bike across Africa, China, South America and other places during their offtime, witnessing first-hand the lives that he previously had been capitalistically judgmental of in a manner keeping with what a boy in Cold War-era suburbs may have been raised to believe.

“Losing It” is my favorite song on the record, however. It is an odd-time prog ballad, mostly synths of various prescriptions anointed with orchestral percussion from Peart and electric violin from Ben Fink, who would later go on to collaborate with Lee on his lone solo album in 2000. Lifeson’s guitar seemingly appears from nowhere, having slowly crept up in the mix from gentle dappling textures to full chords to eventually joining in the melodic arc. The results are surprisingly close to something Genesis might have done on records like Foxtrot or Selling England By The Pound, leaning deliberately toward a sense of the pastoral symphonic grandeur that Tony Banks and Steve Hackett would produce for Genesis in their prime years. The lyrics concern the struggles of an artist losing access to their craft, be it through age or physical disability or lack of inspiration. The pain is palpable; that the group would make a point to play this song on their very final tour, one that was marked by Peart’s growing joint struggles and the strain on Lee’s voice palpable over decades of singing challenging material, only twists the knife more sharply.

It’s strange to consider album closer “Countdown” a letdown. It has a strong cinematic build, a synth ostinato gradually adjoined with the now-standard lightning crackle of impressionist guitar chords and emphatic stating drums. If anything, “Countdown” feels perhaps the closest to previous songs like “The Camera Eye” or portions of “Red Barchetta,” more closely aligned with that approach to progressive hard rock showcased on previous albums. Perhaps that is why ultimately it feels something like a minor letdown; it is an otherwise strong song, but after a wild show of forward-thinking work, having a song that feels so deeply rooted even in their very recent history as a closing statement for Signals feels certainly like a minor misstep. Still, what a hell of a misstep to make; the song is an absolute highlight of the era and closes out one of the most undeniably strong records of the band’s career not just thus far but overall, managing to blend brilliantly the cerebral pop-rock of their future with the intense and knotted stargazing prog rock of their middle years and the driving hard rock that was always their bedrock.

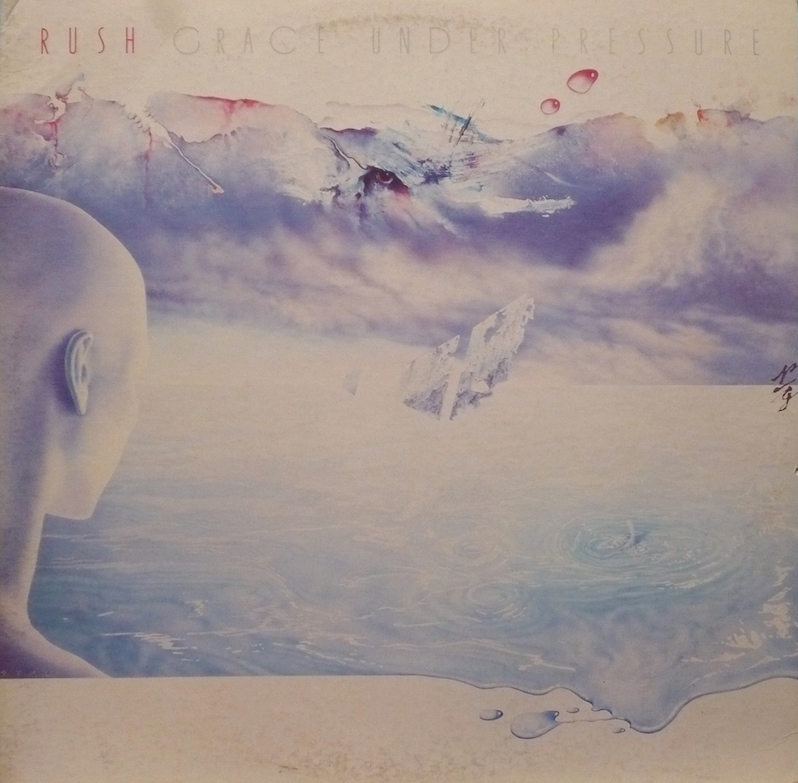

Grace Under Pressure

Grace Under Pressure, the group’s follow-up to the commitment to the sea change of Signals, left an impact off the bat sheerly for the fact that it’s the first record since Fly By Night to not feature Terry Brown as producer. Brown had famously been somewhat alienated by the group during the Signals sessions, pushing back with varying degrees of insistence against their modernization, be it with their increasing use of synths and sequencers or in their genre experiments. The group took note and, without malice, chose instead to pursue other voices from the production chair for future work. Still, in many ways this was the final severing of the anchor line for Rush, moving away from the producer that had nurtured and developed the band as well as infrequently playing as a fourth member in the studio during their most explicitly prog rock days for the unknown landscapes that lay tantalizing before them. It’s hard to disagree with the group’s logic; their sense of identity had only increased over the course of their recording career, the youthful effort to emulate their idols and sharpen their technical skills giving way to the more mature impulse to explore the potentialities of songwriting. Viewing the life of the band’s recording career as a human life, they had passed through puberty, lingering in young adulthood, with the only stage left being to sever that final comforting connection to the world of their childhood to dive fully into the mysteries of adulthood.

“Distant Early Warning,” named after an anti-nuclear missile defense system, explores the timbral and songwriting ideas of Signals but this time with a much more cognizant blend of synths and basslines from Lee as well as a finer balance of the guitars and the synths. Lifeson by this point had a full album under his belt of the band’s new synth-oriented period and had sharpened his tonal ideas a bit more, using a treble-heavy tone that alternates between cutting clear through the synths in a way only a guitar can to blending in chorused synthetic bliss. The dancing sequencers balance against a thick, mid-range bass tone, fusing the maximalism of neon-soaked sweat-scented pop with driving rock. This is all balanced against Peart’s continued vocal efforts to explore lived human emotions, the song structured as a human plea for connection in the midst of an increasingly fraught and alienated world rattled by nuclear tensions, Cold War paranoia and capitalist excess. Signals may have hinted at this broader reconsideration on the part of Peart and the band vis-a-vis their cultural grounding, but Grace Under Pressure devotes itself to exploring the conceit of human connection, community, anxiety and contradiction in the vice-grip of the paradoxical tensions of the Cold War. Rush have always made sure their opening tracks function as thesis statements for the record, from the macro-scale openers of albums like 2112 and Hemispheres to the laserfocused new wave-inspired prog of “The Spirit of Radio” and “Tom Sawyer.” Everything about the song is about building anxiety and tension, from the gradual ratcheting of sonic energy and layered sounds to the sharp guitars and climbing melodies.

That Grace Under Pressure segues right into “Afterimage” is a sharp twist of the knife. The anxiety of “Distant Early Warning,” with its cries of “I see the tip of the iceberg / and I worry about you” are suddenly turned to the anguish and grief and loss as Geddy sings, “Suddenly, you were gone.” This was the group’s second album in a row to feature a song grappling with grief, but this time its placement on the record put it right at the beginning, its lyrical focus shifting from losing access to creative gifts to permanently losing people we love. Sonically, it’s of a piece with the directionalities they pursued on Signals, with Lee largely abandoning the bass for a wall of synthesizers and sequencers. However, like “Distant Early Warning,” Lifeson’s tone cuts through significantly better, often sounding like a livewire, living electricity replicating the sharpness of anguish slicing through the synths which seem to replicate the suffocating totality of grief.

Rush’s commitment to dystopic darkness married in paradox to cold and inhuman dance grooves continues on “Red Sector A,” a Giorgio Moroder-esque Italo disco synth-driven song about the Holocaust lyrically derived from the experiences of Lee’s parents in the camps. Here, the inhumanity of those mechanical grooves with their synthesized drums and perfect sequenced timing replicate the mechanization of death, their coldness and inhumanity challenges by Geddy’s most soulful and impassioned vocal performance perhaps of the band’s entire career. Given the subject matter, so intimately tied to his family and cultural history, it’s beyond fitting. Here, the instrumental break which for the previous two songs had symbolized the stark clouds of anxiety and grief here represent the paradoxical punishment of hope, mirrored in the line “Are the liberators here? / Do I hope or do I fear?” That the music returns quick to the cold-sweat apocalyptic anxiety of that hellish place, with its refrain of “Are we the last ones left alive? / Are we the only human beings to survive?” is haunting, almost ghoulish. It is here that the seriousness of the title and its implied conceptual thread are made starkly clear, the titular pressures being not mundane concerns but the more grave matters of Cold War Western paradox and anxiety, the suddenness and impossibility of grief, and the nihilistic experiential black hole of the Holocaust. The graces, then, are not thin and cheap responses but instead the mere human survival, Lee’s voice and Lifeson’s guitar against the mechanized terror of synthesizers and Peart’s almost too-perfect drums.

“The Enemy Within”, the finally-delivered first movement of the “Fear” suite, is a relative breath of relief, a mere new wave/ska track concerning the way our own fears can rattle us. This completes the triptych as Peart originally envisioned it, each of the three parts exploring, in order, our own fears’ effect on us, the fears of others weaponized against us, and social fears begetting social control and pariahs. The suite in its original three-part form would be played on the tour for Grace Under Pressure but from then on the songs would be kept separate, similar to how the formerly conjoined books one and two of “Cygnus X-1” would never be played as back to back again following the Permanent Waves tour. In keeping with the thread of the movements growing darker and more abstract over time, this is the most concrete and upbeat, a bouncy and bright number that closes out the stark and growing existential terror of side one of Grace Under Pressure on a relative light note. New wave and ska elements once more seem to resemble anxious energy in cocaine-scented fugue states, like the crest of a manic wave. “The Enemy Within” is strangely upbeat for its subject matter and placement on the record. On paper, this is perhaps a failure to cohere more fully to the otherwise stark rattling darkness of the LP prior to this point, but on a song-level, it again produces a work that challenges the most ardent Rush-hating music fan, the type that views them as pretentious, over-written, too conservative and radically unhip, to deny the sheer pop power of the tune. Its video would also famously be the first video ever played on Canadian music channel MuchMusic, their equivalent to MTV and the like.

Side two feels for the most part disconnected from the conceptual thrust of side one. Its opening track is “The Body Electric,” another science fiction fable from a group after having gone a full autobiographical concept record without one, focusing on a plastic android’s escape and struggle for sentience. It’s perhaps the deepest into new wave the group would ever dive, albeit the same kind of prog-flecked new wave of groups like A Flock of Seagulls and The Buggles, the latter of which were so proggy they found themselves recruited to become members of Yes with Geoff Downes now being technically the longest tenured keyboardist of their history. Despite being a satisfying song, it is a puzzling choice to lead the second side. It fairs well in the era of CDs and streaming where it suddenly becomes a middle track, allowing its lack of strength of a side-opener to fall away and reveal the charms and cybernetic desert mirrored-shades cool of the tune without pressure. Still, it’s hard not to believe that this song’s placement was part of what led to the record’s relatively low estimation by Rush fandom for years and even decades after its release.

“Kid Gloves” is a guitar-driven prog tune in 5/4 that feels most directly indebted to Permanent Waves and Moving Pictures, the synths largely absent aside from a few supporting pads to fill space. It’s a sharp pick-up from the previous track, showcasing a Rush performing songs of the style they’d spent years in the 70s mastering ‘but with the modern tricks and technology they’d been learning. The results are immediately obvious; it is not that the rest of the songs prior or after this on the album are bad—far from it—but naturalness and comfort in this song makes it immediately pop off the page. The fact that the group had gotten so much better at crafting big pop hooks and learning how to arrive at a more balanced melding of synthesizers and Alex Lifeson’s iconic guitar voice only strengthens “Kid Gloves.” It’s frustrating to see more conservative Rush fans, the type that turn their noses up at anything with a whiff of new wave, show favor to some weaker cuts from the group’s ’70s material over this song given how strongly the DNA of those songs is present here, just sharpened. Even fans of this LP, of which there are many now, seem to largely look over this song when discussing the merits of Grace Under Pressure. It seems almost certainly due to the fact that it is sandwiched between the two weakest cuts on the album, the second of which, “red lenses,” is easily the worst.

Over the years, I have struggled to come to terms with “red lenses,” a song that is annoyingly always rendered in all lower-case and ideally red font when able in some kind of proto-vaporwave aesthetic gesture. To its credit, its more abstract arrangement, going between a Police-inspired bridge and a more orchestrated new wave chorus and especially its vaguely Eastern-sounding almost New Age/prog instrumental bridge, feels like a direct precursor to “Mystic Rhythms,” the album closer from their next LP Power Windows. But where that latter song builds a more technologically synchronous prog whole, “red lenses” indulges in sometimes aimless and gainless wordplay that belies the group’s sense of humor (otherwise on short supply here) but to the detriment of the tonal cohesion of the album. There are spans of the song, such as the span from 2:05 to 3:41 where suddenly the group decides to focus on a more somber and meditative programmatic orchestral arc to their playing, that are downright gorgeous, strong contenders that the band never lost their urge for progressive music but only sought to keep it modern and fresh versus their already at-the-time backward gazing figures in the late ’70s.

Then the downright goofy new wave funky comedy verses return and quickly the goodwill is squandered. The song bears a striking resemblance at least in intention to “Who Dunnit?” from Genesis’ 1981 album Abacab, having a similarly half-joking tone and deliberate foray into challenging new wave-driven tonal space. Where Genesis’ song succeeds by leaning deeply into the avant-garde surrealism of their tonal and timbral choices, mixed with a hard swinging groove, Rush feels too loose for it to work. This is frustrating because the group clearly has a lot of fun playing it, sounding relaxed and in the groove, and the chorus and instrumental span are deeply moving, but the verses are just too annoying for it to really work. We know the band loved weed and given that it was the ’80s and they were white we can assume they tried cocaine once or twice, but very few songs in the group’s history reek of drug-adled bad decision making as “red lenses.” That it became a concept staple for the entire remainder of their synth period is a cruel mystery; I routinely find myself wondering if this song along is why so many Rush fans loudly decry their ’80s material that otherwise seems so endlessly compelling to everyone else.

That the album bounces back and closes with a song as strong as “Between the Wheels” is a strange but gratifying mercy. “Between the Wheels” is a powerhouse of a track, returning to the same cybernetically taut, proggy and mercilessly dark mixture of ska and arthouse new wave that Rush showcased on cuts like “Afterimage” and “Red Sector A.” The verses linger in a dark minor key ska vamp, long shadows in gothic relief cast against the walls before shifting to an up-tempo rock groove not unlike the similarly car-themed “Red Barchetta” (seemingly also referenced in the sci-fi oriented “The Body Electric”) but here delivered with a sharper emotional sensibility. The lyrics fixate on the fickleness of life both on the micro and macro scale, from personal wealth and destitution to golden eras of nations and periods of intense war and loss. This is a perfect counterpoint to “Distant Early Warning”, functioning in summation and recapitulation of the themes that earlier song established as thesis to the album. It, along with the first three songs of the album, form the undeniable core of the conceptual sweep of the album, a series of dark realist modernist prog rock portraits, ending on the fatalist images of this sounds excessively morbid pre-chorus.

Grace Under Pressure‘s oddity is deepened by the fact that, despite the slight weakness of “The Body Electric” and the major weakness of “red lenses,” it has since become viewed by fans as perhaps their greatest record. This flummoxes those with the band through their rise, tending to prefer either acrobatic hard rock classics like Fly By Night, out-and-out prog rock behemoths like A Farewell to Kings or the more balanced hybrid sound of Moving Pictures. The rise in acclaim Grace Under Pressure has seen can be traced to the broader acceptance of synth-based music and the various subgenre gifts of the ’80s in the decades and generations since, with synth-pop and traditional heavy metal achieving an iconic and overwhelming potency. It would be understandable for fans of the time to be put off by the second side’s brief wobbles. Given that Signals is still often considered a seminal record to more conservative fans and Grace Under Pressure is not, the source can’t really be the synths as they say, especially given that Lifeson’s guitars are more present here. Still, while there is a profound strength that the band tapped into with Signals‘ autobiographical arc, which saw them turn Peart’s sharpening lyrical eye to the concerns of their real lived lives, Grace Under Pressure transformed that new approach by and large into a dark and more somber effort, one that carries a substantially more potent emotional punch in the heart. This record far and away is the best starting point for those that, whether through a punk upbringing or general iconoclastic sneering, tend to view Rush as overly conservative hookless dorks; I challenge you to make it through the soul-shattering mechanical darkness of “Red Sector A”‘s real-life familial Holocaust tale and its darkling view of the shape of life and walk away believing the group is incapable of savage emotional insight.

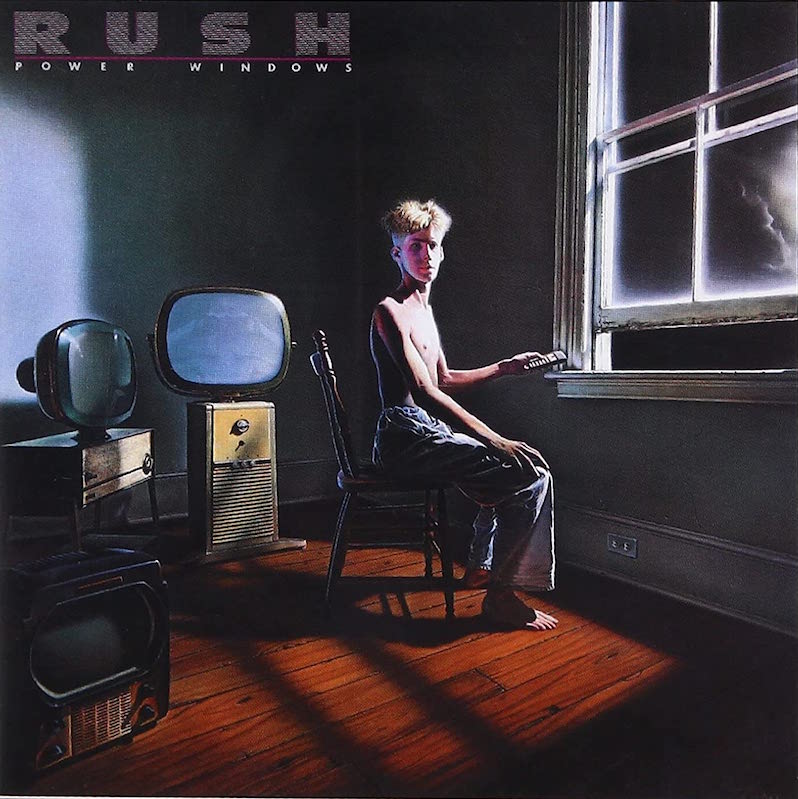

Power Windows

Power Windows is notable for a bizarre split of perception between fans, critics and the band. The band were quite vocal in interviews both preceding and following that its conceptual thrust on a musical end was two-fold: first, to have a more synchronous balance of guitars and synths, given what they’d learned about the role both could play in melodic lead and rhythmic contexts; and, second, to on-board a producer early on in the project’s lifespan, letting that additional creative voice push them into unknown creative domains that they felt they hadn’t quite reached with Grace Under Pressure. This is strange from the outside, given that Power Windows is generally perceived as their most synthetic offering in the group’s entire discography, let alone this period. However, the two tend to answer each other regarding the record.

Discarding the opening and closing tracks, each of which have their own distinct timbre and approach, the middle six songs of Power Windows are broadly speaking their most pop-oriented material to date, foregrounding arena-sized synth-pop melodies that, with a brief vocal change, wouldn’t feel out of place in the hands of modern groups like CHVRCHES and Alvvways, let alone contemporaries like Ultravox and New Order. There is still a skeleton of prog rock and those trademark Rush chords from Alex, the busy Yes-influenced bass work from Geddy and the architectural structurist drum beats from Neil. But by having an additional creative voice in the production chair as early as the band did left room both to shape the tones of the instruments to better fit that technicolor neon gleam of synth-pop and allow production choices they would have been reticent to indulge before. The group up until Grace Under Pressure had shown tremendous discipline, not allowing any additional players in a live setting and then from there limiting themselves in the studio to only that which they could feasibly reproduce live with just the three of them. At times, this meant Lifeson and Lee both operating synth foot pedals on top of Lee’s triple-duty on bass, keys and vocals, with Peart integrating a bevy of electronic pads and triggers both for his hands and feet into his kit on the Grace Under Pressure tour. It was on that tour that their live shows became the jaw-dropping technical exercises they came to be known for, melding both raw technical ability and the cross-discipline technological web-work of triggering/playing all of those elements themselves with no backing tracks.

One of the primary changes on Power Windows was new producer Peter Collins pushing the band to temporarily abandon this ethos, allowing him to bring in string players on a number of tracks as well as a number of layers and overdubs that swam far beyond what any mere mortal could ever hope to play live. The first things the ear catches in the context of those six main body tracks is a combination of the density of the production paired against the way the guitars and synths alloy themselves against each other. This has more to do with finally getting a producer in the chair who better understood both the mixing range of the synths the band were deploying as well as having a keen ear for pop guitar production, finally able to give more focused attention to shaping Lifeson’s tone to be able to seamlessly pop out of the mix when called for before sinking back into the glorious hi-fidelity prog/shred-pop.

Plucking any of those middle six tracks out for individual focus like what’s been done for earlier records feels strongly like a surefire way to misinterpret the record. These are perhaps the greatest pop songs of the band’s career, effortless in their fusion of prog chops and the strongest pop hooks they arguably ever put to tape. The group clearly saw a commonality in the scope of vision of prog and pop music, both wanting to span the vast eternities of the imaginative capacity of the listener while painting in every color available, the programmatic intent of prog met on the battlefield with the evocative grandeur of perfect pop chord placement and production. The group’s genre experiments here are, at least for those middle six, smoothed out into a seamless and unified whole, with the various elements cohering to a single gleaming whole. Even the lyrics of those middle six felt like a perfect honing and recapitulation of the themes of the past two or three albums, with songs like “Emotion Detector” and “Middletown Dreams” evoking paralytic star-gazing combination of the suburban ennui and yearning of “Subdivisions” and songs like “Territories” and “Marathon” feeling like nods to the global realism-meets-psychological superstructures of “Distant Early Warning” and “Digital Man.” “Grand Designs” is nominally a critique of the mass produced aesthetic of pop-music but those elements feel subliminal compared to its parallels to the mechanized horror present in Grace Under Pressure, while “Manhattan Project” is in keeping with “The Body Electric” as the explicit story-telling song of the record, albeit here the deeply-researched true story of the creation of the nuclear bomb, an invention the group widely lamented on the previous two releases.

If Power Windows were merely its middle six, spanning “Grand Designs” to “Emotion Detector,” it would likely be considered among the group’s best in my estimation. This type of hyperfuturistic prog-pop is impossibly in vogue now and the directionalities of genres like neo-prog and synth-pop validate the perfected experiments found here. That they chose to play a vast majority of the album for the first time since its release for their Clockwork Angels tour, the second-to-last the band ever embarked upon, should be read as a late-stage validation of the record’s strengths, both in their eyes and (based on that tour’s warm reception) the fans’ as well. Why then does it seem to be so widely derided even among fans of Rush’s post-Moving Pictures work? It is no wonder that the more conservative classic rock-derived prog fan might turn their nose up at this fare, given its clear futurist nostalgia-denying intent, but what of those that tend to enjoy or even prefer the band’s more tightly-bound and ambitious prog/pop-rock years?

The fault lies with opening and closing tracks “The Big Money” and “Mystic Rhythms.” The first is the band’s most cocaine-scented high-energy funk-pop track, feeling like a hybrid of 1984-era synth-wielding Van Halen and 90125-era Yes. It is perhaps the group’s most overwhelmingly ’80s song as well, from the guitar hits to the popping funk bass to the background sound effects (largely produced by guitar but with a few synth splashes thrown in for good measure). The chorus and bridge align the song more solidly with the panoramic synthetic neon intent of the rest of the record, and the guitar solo bleeds all the unique wild-lightning voice that all of Alex’s guitar solos from Permanent Waves reveled in, but the verses contain so much exuberant cocaine bounce that “The Big Money” clearly sets itself apart from its peers in terms of energy level. The energy of the record gradually decreases track by track, setting further and further into an image-rich ambient headspace, until the finale “Mystic Rhythms.”

“Mystic Rhythms” is fittingly placed at the end of the record not just because of that streamlined sense of controlled energy and pacing of an album, starting with “The Big Money” before settling into a past-midnight spiritualist meditation; it also happens to be the album that most clearly presages that which would come next. If “The Big Money” is their modern synthetic prog attempt at the high-energy guitar-driven rock singles of albums like Permanent Waves and the middle six are their songwriting voice of this era crystallized and perfected in gleaming pop alloy, then “Mystic Rhythms” is its experimental deconstruction. Technically, this had been attempted before, with “red lenses” being a hodge-podge of interesting and fruitful experiments in abstraction and groove in the context of Rush, but here they come together far more superbly. One of the most common responses to conservative Rush fans who turn their noses up at the work the group would turn in after Signals is the throughline of the shorter tracks from their debut up to the synth age, all of which share a similar character and approach to writing condensed material in the context of an undeniably proggy band. “Mystic Rhythms”, however, feels like a band molting, almost more inclined to the arthouse post-prog of later-day Japan and the following solo material of its guitarist/vocalist David Sylvian or perhaps Peter Gabriel’s increasingly world-music inspired art rock/pop work. It also happens to be one of the most resolutely moving Rush songs, leaning in without hesitation to its admittedly almost silly premise and finding great reward in doing so. Its melody soars and sings over the thrumming tattoo of world music-driven new age beneath it, finally delivering the kind of synth-driven hippie paean that Yes before them had mastered in the ’70s.

Both “The Big Money” and “Mystic Rhythms” are well-regarded by fans, critics and the band alike, finding themselves concert staples following the release of Power Windows while most of the album would disappear from setlists. Why frame them as the reason for the record’s souring in perception compared to its middle six? That has more to do with the tonal shifts those songs induce on the record as a whole. “The Big Money,” despite containing more thoughtful and meditative passages in its chorus and bridge, is psychically dominated by the energetic bass-driven rave-up of the verses, while “Mystic Rhythms” presents an abstracted and deconstructed new age ambiance that is clearly a guiding image for the production of the rest of the songs on the album but is largely absent from the actual structures of the songs. To a discerning ear, their usage as bookends for the album feels a keen and intelligent choice, one representing the roiling rock trio energy of the group and the other the programmatic synth-pop/prog rock hybrid with the main body of “Grand Designs” to “Emotion Detector” being the perfect hybridized forms crystallized in between.

I’ve come to view the album as a consistent favorite, ranking in rotation in my top-three Rush albums (the other two of which have yet to be discussed), but even this position was late in development. I found after several listens that I had no firm grasp of what the middle songs really felt like, knowing well the opening and close of the album while the rest seemed to melt away. I would start the album on track 2 and turn it off at the close of track 7, refusing myself the pleasures of the two singles of the album, until eventually as those songs began to individuate themselves to me, they quickly became not just well-regarded by me but quickly supplanted even Moving Pictures or underground favorite Grace Under Pressure. They represent in my mind a perfect world, the perfect gleaming metal alloy of prog chops with pop hooks and songwriting, united by their absolutely colossal imagistic intent. The deeper reason I didn’t dive into the individual songs of this record as before has more to do with the way those middle six live as an extended song-suite in my mind, the perfected form of this era of Rush, encased by two containing extreme forms.

Power Windows‘ low reputation among many fans and critics obscures a small number of additional interesting facts. First, “The Big Money” is Peart’s first explicit disavowal of the libertarian ultra-capitalist impulses that had come from Ayn Rand’s influence, naming in no uncertain terms the cold inhumanity of the movement of capital; without reason, without compassion, without remorse. Likewise, “Mystic Rhythms” is the first time Rush grappled directly with spirituality, a notable event from a band of avowed atheists. It is admittedly a more modern sense of spiritualism, one that privileges the intensity of experience, memory and sensation over the supernatural, in keeping with their previous depictions on more fantastical songs like “2112” and “Hemispheres.” Power Windows also partly challenges the previously purely dialectical arc of Rush albums where each new album was spawned as a response to the one directly before it while offering the clear fundament of the album to come. The middle six songs of Power Windows act as a functional Rosetta stone for the remaining years of the group’s life until their hiatus in 1996, with the records from Hold Your Fire to Test for Echo feeling largely derived from the finally-mastered pop/prog/rock fusion songwriting the group displays here.

Hold Your Fire

Rush must have sensed some leap in their capabilities with Peter Collins, given that they retained him for Hold Your Fire. They likewise retained Andy Richards, their studio keyboard player for Power Windows, thus featuring the first time in their post-Terry Brown era of recording two consecutive studio records with the same creative lineup. Hold Your Fire reads as very much a reaction to Power Windows, eschewing a synchronous and harmonious shape to its songs like on that previous record in favor of pursuing seemingly every potential forward path from it they could think of. Hold Your Fire is in turns more cerebral and more simple, more progressive and more poppy, more stripped-back and more experimental, with no strong through-line to guide it. As a result, some find the creative span of the record to be a boon while others read it as a scattershot mess of an album made up of decent songs but without the same sense of internal logic that seemed to drive prior records. Still, the musical thesis of Hold Your Fire, that of isolating and expanding to full song-length the sonic ideas that before on Power Windows had been alloyed into a perfect synchronous whole, produces a number of fascinating ideas, approaches and finished songs in a kaleidoscopic span. The intent of Hold Your Fire seems, in retrospect, to expand more fully on what the post-Moving Pictures era of the band in general seemed to be focused on internally: seeing the full extent of what these three players could do given they set their minds to it.

“Force Ten” is a gloriously bizarre song, seeming to take at face value their stated intent post-Moving Pictures to cram as much song into as little a space as possible. Its opening passage feels confused, starting with first a choir, then a distorted guitar, then industrial sounds, before finally settling into a post-Power Windows groove that moves jaggedly into a “The Big Money”-style upbeat funky pop-rock track. All of this transpires in about 30 seconds—a whirlwind of musical ideas that feels like a hypercompressed prog epic, movements in moments. The chorus matches the upbeat pop-rock with an open “Mystic Rhythms”-style ambient prog vibe while the second verse adds coked-out synth sequencers to the mix. On paper, this shouldn’t work, should be as tedious as the final three minutes of “Xanadu” in their excess; but it’s not. It’s glorious. This is one of the strange wonders of Hold Your Fire, which one moment contains some of their best material of this era of the band and moments later the worst.

That the album then moves to bare-bones pop-rock AOR tune “Time Stand Still” is a perfect example of the wheel of wonders of Hold Your Fire. That the song is brilliant is another. Despite strong showings on their debut, side two of 2112 and the briefer tracks on A Farewell To Kings, Rush fans are quick to forget that this kind of direct ’60s-influenced pop-rock has always been in the band’s blood. The slight country lick in the chromatic upward motion of the guitar in the verses, the almost R.E.M. vibe to the guitar work aside and the return of “Mystic Rhythms” vibes in the cooler temperature pre-chorus blend to pop perfection, almost tricking you into thinking you aren’t listening to Rush. If it weren’t for the bridges (or the presence of Lee’s immediately recognizable voice), you could pass this song off as one of the great AOR tunes of the era, up there with the top cuts of 80s Heart and Toto.

“Open Secrets” would be a perfect fit for that magical middle six of Power Windows. In shifting movements, it evokes Marillion, 90125-era Yes, the peaks of ’80s Pink Floyd and more. They fully indulge that quintessential ’80s sound of gated reverb, burping bass and the guitar tone that had become Lifeson’s signature, a clear and cutting tone that sears and sizzles like lightning through a summer sky. There’s just so much ear candy in the song and its arrangement, guitar parts coming in and out, brief open spaces, parts shifting bit by bit as bars repeated and rattle on.

The ever-turning wheel of wonders that is Hold Your Fire is notable for being as brutal and unforgiving as it is full of treasures. “Second Nature” is one of those wicked brutalities, a mind-bogglingly cheesy Casio-keyboard demo-esque ballad with some truly awful lyrics attached. There has been a reclamation through vaporwave of the Casio demo sound that pervaded the late ’80s and early ’90s, the hallmark of shopping malls at the peak of their power and the openings of sitcoms we were all forced to watch by workaholic absentee parents. But here, the real thing is just so on-the-nose that it feels emotionally punishing and confounding, sweeping away almost all the momentum the previous tracks built up. Over the years, I’ve gone back and forth in dramatic fashion, either loving or hating this song, with nothing in between. The love largely comes from the chorus, which is another tentative stab at the cleaner guitar-oriented pop-rock approach they would dive more headlong into on Presto and Roll The Bones, but in this context it is surrounded by so much frankly cheesy garbage that it can’t really hope to salvage the song.

The wheel forever turns, giving us “Prime Mover” as the closer to side one, a truly glorious arena-filling song that offers wisely measured dramatics across its span. It’s worth commenting always that when people refer to Rush as a smart band, a cerebral band, especially regarding its lyrics, the intent isn’t (or at least shouldn’t be) to say they stand up to the heights of Goethe and Melville and Marx. Their broader taste in music always belies that they themselves did not fancy themselves somehow lording above all of music but instead mining a specific aesthetic, one that thinks more often about the arc and construction of life rather than specific relationships, not to be better or worse but merely different. “Prime Mover” is an example of when that lyrical and aesthetic approach can provide massive dividends on a songwriting end, matching the detail-rich, prog production-heavy arena pop-rock with turns of phrase that suddenly make the song feel enormous, world-filling, simultaneously intimate and stargazing. The sense of attachment Rush fans feel to Neil Peart and his lyrics severely disproves the notion that it’s all just meaningless pretense; it strikes a real emotional chord with Rush fans, stirs something deep inside even if that thing isn’t always shared by others. “Alternating currents / in a tidewater surge” just has a certain elementalist primitive power to it, a combination of grace and strength matched by the masterful songwriting. If Carly Rae Jepsen covered this now, you’d have legions of avowed Rush haters singing gleefully along to its maximalist pseudo-philosophical open-hearted musings, not because it’s “smart” or “cerebral” but because it is passionately emotive, soaring, great.

“Lock And Key” once more returns to the perfected sounds of the middle six of Power Windows. It matches a hip set of chords, as spacious as they are brooding, bright in timbre in a manner that feels more threatening than comforting, with a set of lyrics that are a sharp indictment of the heinous brutality lurking in humanity. The band wisely doesn’t capitulate to the notion that humanity is inherently lawless and wicked, acknowledging that this wickedness is haphazardly contained. But a song as dark and brooding as this feels natural to arise from Peart’s pen given his increasingly worldliness around this time, both monitoring the news and the horrors it holds as much as his increasing habit of biking through Africa, China and other nations. This act of witnessing the world as it is on the ground level of the common experience in places other than the west shook him deeply, producing songs like “The Big Money” and this one, each focused in ways on the kinds of brutalities we can inflict on one another even through the veiling mask of high civilization which is often the (racist) excuse for endless licensure to violence by the west. When Lee sings, “I don’t want to face the killer instinct,” in the final chorus, set against roaring bass synths and a wailing choir of his own voice, it feels not unlike the climactic moment of a fantasy novel, a true reckoning, the spirit in darkness witnessing the evil crafted by its own hands. It’s powerful, enormous, like glimpsing some gigantic shadow lurking in the shadow of your heart.

“Mission” at first feels like it will settle into “Second Nature” territory, more cheese than its worth. This is a tempting read, one largely built off of how obnoxious the chorus is, feeling too often like the ending credits soaring-synth finale music of some ’80s teen film. But the verses shift away from that almost unbearably on-the-nose approach to the more guitar-driven pop-rock that would come to dominate Presto, plus the killer groove just before the equally killer instrumental bridge/solo section, and the song feels like it begins to work itself back into your heart. That a Zappa-esque section of unison marimba/bass hits follows cements the sensation that there is in fact something here worth preserving, some balance of soft rock, prog, fusion and jangle pop. Indie rock would, over time, seemingly take up these notes and develop upon them deliberately, mining that fusion for all it was worth. But here sadly the mixture, while certainly better and more defensible than on “Second Nature,” is just too muddied with cheese, the obnoxious chorus recurring just a bit too much.

“Turn Your Page” is another of the future-gazing songs of the record. Its opening bass figure feels more directly prescient of the darker, dirtier rock vibe of Counterparts, while large stretches of its arrangement from the bright synths to the particular tone and timbre of the guitars, clean reverb and cutting brightness, feels closer to Roll The Bones. The band seems spontaneously returned to their full and former power here, driving the song forward on the back of the guitar/bass/drum trio format they are best at. On one hand, I’m hesitant to say something like that, given the strength not only of this synth-heavy period in general, home to some of my absolute favorite Rush records of all-time, but also due to the strength of the synth arrangement on this song, which buoys the rock-trio elements by filling in excess space in an unobtrusive but helpful way and even gets a satisfying punchy lead late in the song. At the same time, it’s hard to hear this song in the context of this album, hear how natural and joyful it seems, almost like the notes are bursting free out of them, and not grasp that this is the way forward for the band.

But then we get, inevitably, to “Tai Shan.” Like “Lakeside Park” and “I Think I’m Going Bald,” the band is notoriously harsh on this one. Some fans have picked up that tack, punishing it as one of the band’s worst tracks, but while it’s somewhat regrettable, it doesn’t deserve so much loathing. It’s largely based off of a deeply personal experience Neil had in China, hiking up a mountain with a guide and experiencing a sense of decentering peace that was another step on the road of his move leftward. On that ground, it has some charm, but undeniably the lyrics are suspiciously literal for a penman who even on the same album showed a sublime level of grace. That it’s matched at times with eye-rolling melodic choices that feel just one step shy of racist doesn’t help things much. If you sit with “Tai Shan” and are patient with it, you can begin to grasp what they were going for with the song; but even in those conditions, it certainly didn’t bake long enough.

The other big nail in the album’s coffin is closer “High Water.” At first, it seems promising enough, a funky syncopated drum groove against slowly building sequenced synth riffs and a relaxed vocal that doesn’t overextend itself. But then the chorus kicks in, something that feels almost like a mean-average of the choruses of the tracks prior, and it begins to dawn on you that the group just didn’t have 10 songs worth of finished material worth publishing. There are flashes of promise, and thankfully the song manages to keep from falling into desulatory cheese like “Second Nature” does. That the song doesn’t seem to end so much as stop doesn’t help matters either. This functionally converts the final ten minutes of Hold Your Fire, a full fifth of the album’s runtime, into dead weight, an undeniable contributor to its relatively low estimation within this period where prior perhaps the only dull track on the three records before it is “red lenses”. When you add in “Second Nature” and “Tai Shan,” it brings Hold Your Fire to a 60/40 split of great to troubling material, a balance which earns it a more marginal position compared to its peers and justifies the sonic shift that would come on the following album.

It provides, frankly, a sad end to an otherwise brilliant era, going out with a whimper rather than a bang. There is some world where those four troublesome tracks on Hold Your Fire are either cut or reworked, the tracklist shuffled around to put “Turn The Page” at the end as a clear nod toward the future on the back of a bopping rock tune, and in that world I think not only does Hold Your Fire fare better but the entire synth era of the band in general. In previous eras, the group ended on arguably their best record of that period, the first closing with 2112 and the second ending with Moving Pictures. The synth era seems to reverse that; the group certainly explored different aspects of the sound on Signals, Grace Under Pressure and Power Windows, but each of those three felt like a master’s thesis on those perspectives, spanning the autobiographical intimate prog, darkly mechanical pop and then bright and brilliant fusion of those two ideals. Hold Your Fire feels like a confused set, some songs feeling like high quality cast-offs from those previous albums with little doses of what was to come on Presto included while others were misguided and frankly unbearably cheesy songs lingering too long in a sonic space that seemed to have exhausted itself for the group. Rush is a group that thrives on change; this is the engine that raised them up from hard rock obscurity to prog rock royalty and the same thing that drove them from flamboyant superlative prog rock to nervy (and still quite proggy!) new wave, synth music and arena pop. It is likewise the same force that, at the frustrating and lackluster ending of Hold Your Fire, would cause them to take stock of themselves and hurl themselves once more into the unknown.

This period was for a long time my favorite of the group’s entire career and, depending on my mood, quickly becomes that again. Their second phase, from A Farewell to Kings up to Moving Pictures, is undeniably a brilliant run, but they only seemed to full grasp their own lurking hidden sense of identity by the end of that run, while the period of Signals to Hold Your Fire seemed to revel in it. The first song I heard by Rush when at least I convinced myself to give them a solid go was “2112,” a tune which impressed me but felt like it flagged in its middle span. The next attempt was Moving Pictures, an undeniably brilliant record that unfortunately was driven to cliche by just how much (and how loudly) everyone loved it. It was off of the back of investigating some of the songs that most wowed me off the Rush in Rio live set that I found myself picking up Grace Under Pressure and Signals in one go. They still often form a diptych in my mind, each elaborating on the other, almost as though the autobiographical thrust of Signals blossoms post-“Countdown” into the cold and horrified ruminations of mechanized terror and anxiety born from the Cold War, the Holocaust, and AI, a triptych of present, past and future. That Power Windows would later reveal itself to me to be closer to the evocative core of Rush, that smiling and optimistic youthful and idealistic bountiful core, was a treasure to me, even though I put off getting that record until nearly the very end of acquiring the group’s discography. Moreover, the synth era seems clearly to me to have proved the thesis Rush themselves put forward: if Moving Pictures were to be considered their proper debut, with its prog-minded playing and arrangements squashed into hooky pop-rock songwriting formats, then suddenly everything that comes after makes more sense. Granted, this sense of understanding of the band would find itself undone by the band’s end; such is the mystery of the ever-changing, never-changing sonic heart of Rush.

Support our Site—Subscribe to Our Patreon: Become one of our monthly patrons and help support an independent media resource while gaining access to exclusive content, shirts, playlists, mixtapes and more.

Langdon Hickman is listening to progressive rock and death metal. He currently resides in Virginia with his partner and their two pets.